What was it about those bad-boy poets that I loved so much at 16? Brautigan, Ferlinghetti. And Bill Knott, whose recent death made me think about him and how our paths crossed, twice.

The first time, I was a high school junior attending a week-long poetry workshop at the beautiful old army base Fort Worden, which sits on the tip of a peninsula jutting into Puget Sound. Every day, we students met in seminars with real, true poets. My teacher, Jim Heynen, set out a display of books and invited us to borrow them during the week. On the cover of one book was a cartoon girl, her arms doughy blobs, her eyes red hearts. When I picked it up, Jim told me that the author, Bill Knott, was in residence at the fort, and that if I wanted to, I could knock on his door and talk to him.

I took the book back to my dorm room. In the author photo, Knott seemed worried or distracted, his forehead creased. His hair was messy; it might have been sticky with sweat. Like the girl on the cover, he looked doughy.

Inside was a stream of surreal poems, like this one, in its entirety: “Just hope that when you lie down your toes are a firingsquad.” There was a lot of death, poems about the war in Vietnam, about his own death, like “Goodbye,” which made the Internet rounds after he died: “If you are still alive when you read this,/close your eyes. I am/under their lids, growing black.”

What stirred me most were poems of love and desire, often for a woman named Naomi. In one, he tells Naomi about the “summer fragrances green between your legs.” In another, Naomi’s face is the “altar where my/heart is solved.” In another, “I breathe your/heartbeat, Naomi.” I wanted to be loved like that, to love like that.

I was afraid to bother the famous poet, but I went anyway. I walked across the fort on a misty afternoon and knocked on the door of his cottage. Long pause. The door opened a few inches. Knott looked just as disheveled as in his author photo.

I told him I was at Fort Worden studying poetry, and that my teacher had suggested I come buy a book from him.

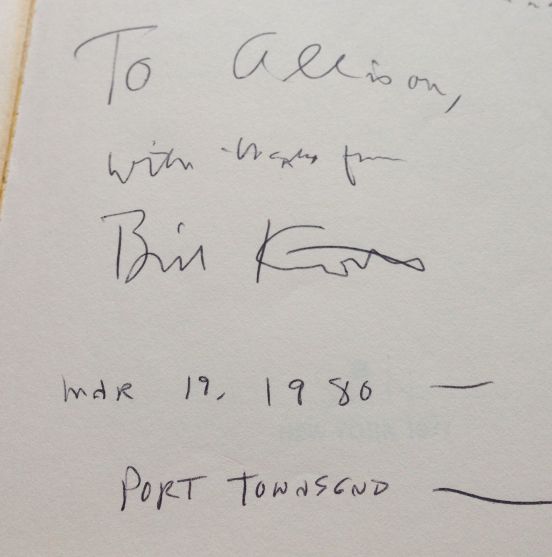

He asked my name and left the doorway. Through the crack in the door, I could see dozens of copies of the book I’d borrowed spread across the floor. When he returned, it was with a copy of his book, signed. He refused to take any money. I was delighted, when I got back to my room, to see that it had a list of poems on the inside flap, as if he had used this copy for a reading.

Almost a decade later, I started my first classes in Emerson College’s M.F.A. program as a fiction writer. Knott was the poetry professor there. Throughout my time at Emerson, he was a kind of apparition, wandering in a raincoat through the halls, not looking at anyone. Still, his presence reminded me of the poet girl I’d been once.

What I wanted then was to be one those bad-boy poets, striding through the world with all that passion and power. There were bad-girl poets, too, of course; Anne Sexton was one I read at the same age. She had the passion, but her power sometimes seemed compromised. I wanted more. It would be some time before I found Sandra Cisneros, Marilyn Hacker, Jessica Hagedorn. Women who could stride like that, burn as bright.