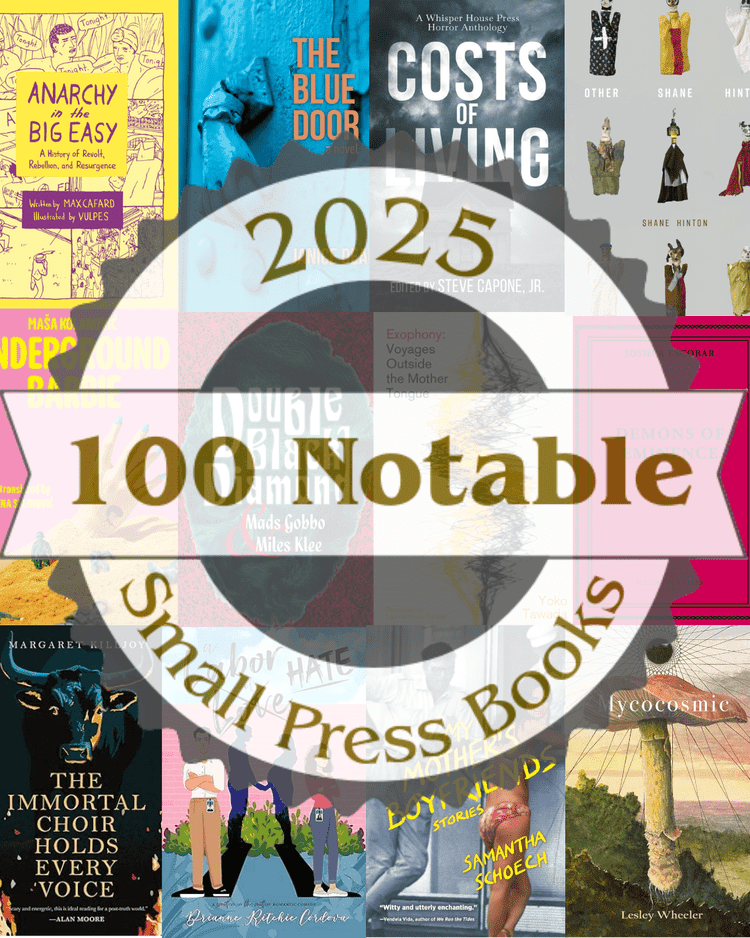

Today LitHub has published a list of 100 notable small press books of 2025, and I had the great honor of choosing two of them: The River People, by Liz Kellebrew, and Sixty Seconds, by Steven Mayfield.

When the call came about a year ago to participate in the project, I signed up, happy to get involved in something that would jumpstart my reading. I had been struggling to read for some time.

In 2023, according to my Goodreads list, I read only two books. I remember listening to them, walking my dog around the neighborhood, crying through some of Sequoia Nagamatsu’s How High We Go in the Dark and pausing Kiese Laymon’s Heavy to absorb his astonishing use of language and the welling of emotions is elicited.

Only two books? That can’t be. Maybe I forgot to post some.

Still, I know my reading time plummeted in recent years. A pandemic ravaged the world, and then my father died suddenly, my mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and our basement flooded and needed to be gutted and restored. Overwhelmed is one word for it.

But this year I was determined to carve out time for something I have always loved to do. For the project, I was required to choose three books to forward to the committee that determined the finalists.

In the spirit of this project, here are a few other small press books I loved this year, not all of which were eligible to be included because they weren’t published in 2025:

- Myriam J.A. Chancy’s Village Weavers (Tin House) is a gorgeous novel about friendship and how it changes over time. Two girls grow up into a world that treats them very differently.

- In the title story of E.P. Tuazon’s collection, A Professional Lola (Red Hen Press), a family hires a woman to pretend to be their grandmother. She knows everything their grandmother knew. How is that possible?

- The stories in Carrie R. Moore’s Make Your Way Home (Tin House) begin with a family curse from the past and end in an apocalyptic future. In between, women and men leave home and return, seeking love and connection.

Thanks to Miriam Gershow for doing all the hard work of making this project happen. Her novel, Closer, was published this year, and I can’t wait to read it.

Speaking of Goodreads: This year I decided to give five stars to every book I read. Writing books is hard work. Writing a disappointing book is hard. Writing a fantastic book is hard. And giving three stars — or two or one — to a work of art, no matter how poorly executed, just seems wrong. Well-done, writers. Five stars to you all!